This past Veteran’s Day I had an extraordinary experience at MoMA. Aaron Hughes, an artist and Iraq War Veteran, invited two small groups of strangers into an intimate exchange: he made tea for us. He made tea for us in what might seem a very strange place within the museum, on a bridge next to MoMA’s Walid Raad exhibition, near Take an Object, and in proximity to Soldier, Spectre, Shaman: The Figure and the Second World War one floor above—all of which include work that reflects artists’ responses to war. Walid Raad, a friend of Aaron’s, was excited that this would take place near his installation.

Posts by Wendy Woon

Learning from Brazil

View of the Niterói Contemporary Art Museum as seen from the Maquinho, the Museum’s Community Art Center. Photo: Pablo Helguera

In this age of facile and constant communication—when you can Google and search anything you need to know, and e-mail or Skype with any one of your colleagues globally—the question arises: Why travel abroad to research?

On a recent research trip to Brazil, I was reminded of the reason by the astute Luiz [Guilherme] Vergara, former director of the Niterói Contemporary Art Museum and professor of art at the Federal University of Niterói: “Geography is everything.” This he noted as we looked out from a community center high up on a mountain at the base of a favela, overlooking a breathtaking view of a bay and the Niteroi Museum, a superb Niemeyer-designed spaceship-like form. The museum and the center work closely in tandem in the community.

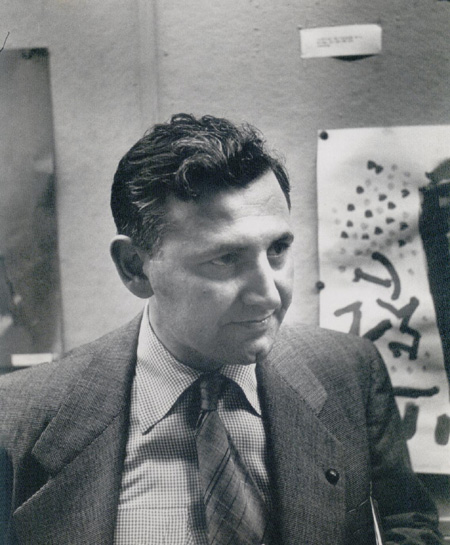

Mining Modern Museum Education: Briley Rasmussen on Victor D’Amico

I often to try to imagine what it was like for MoMA’s first director of education, Victor D’Amico, to build a new, expansive education program dedicated to art with a radically different modern aesthetic at a time when the public was hard hit by the Great Depression.

Mining Modern Museum Education: Kim Kanatani on Hilla Rebay

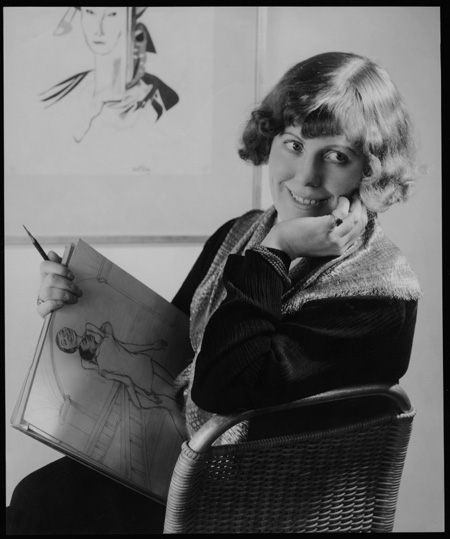

Hilla Rebay in her Carnegie Hall studio, 1935. The Hilla von Rebay Foundation Archives. Photo: Eugene Hutchinson.

I first discovered Hilla Rebay while reading a fascinating book about the life of Peggy Guggenheim, Mistress of Modernism by Mary V. Dearborn, who happened to be my office mate while I was New York City Scholar at the Heyman Center for Humanities at Columbia University several years ago. Peggy’s life was filled with a cast of interesting art world characters, but Hilla Rebay was clearly someone I needed to know more about.

Mining Modern Museum Education: Kelly McKinley on Arthur Lismer

It’s a commonly held notion that a Canadian can be easily identified by the end-of-sentence “eh?” However, true connoisseurs of all things Canadian know that what separates citizens of the north from the south, the true identifier, is that when naming someone notable, the name is followed by a knowing nod and the enthusiastic comment “Canadian!”—as in, Peter Jennings (Canadian!), Brendan Frazier (Canadian!), or Eugene Levy (Canadian!). The impulse to not only include Canadian cultural contributions in the broader American context, but to distinguish them, is deeply ingrained.

For this reason I thought it important, when planning Mining Modern Museum Education, an upcoming panel discussion on four seminal figures in early- to mid-twentieth-century museum education, to consider the significant contributions of my fellow Canadian Arthur Lismer. An iconic Canadian artist of the modern era (Group of Seven), Lismer was also an influential museum educator whose work in this field merits investigation.

Mining Modern Museum Education: Robert Eskridge on Katharine Kuh

On June 25, MoMA will host Mining Modern Museum Education, a panel discussion on four seminal figures in early- to mid-twentieth-century museum education: Victor D’Amico, Hilla Rebay, Arthur Lismer, and Katharine Kuh. The next few blog posts will provide short synopses of what each panelist will discuss, as well as key thoughts by the prominent museum and education scholar George Hein of Lesley University (Cambridge, MA) on the major influences on modern museum education, including the seminal work of education reformer John Dewey.

Below, panelist Robert Eskridge, executive director of education at the Art Institute of Chicago, addresses the influential interpretative work of pioneering art historian, curator, and educator Katharine Kuh.

Mining Modern Museum Education

Photo by Nancy Bulkeley. Cover of "The Questioning Public," a bulletin produced by The Museum of Modern Art. Fall 1947, Issue 1, Vol. XV

In Spring 2006, when I was preparing for my first interview for my current position as deputy director for education at MoMA, I spent some quality time with a fascinating book: Art in Our Time: A Chronicle of the Museum of Modern Art.

A Room with a View

Installation view of the exhibition Sculpture in Color (May 18, 2009–January 11, 2010), featuring three 2006 polyester sculptures by Franz West—Maya’s Dream, Lotus, and Untitled (Orange). Photo by Jason Mandella

Long before I began working at MoMA, I happened to sit next to the former wife of a renowned artist at a dinner marking his posthumous retrospective. I asked her awkwardly about how she had met him, and with tenderness she painted a memorable picture of their first encounter, which centered around MoMA. The year was 1959, and she, a young woman working at the membership desk, was nudged on by a coworker to introduce herself to a security officer who was in the Sculpture Garden, guarding a geodesic dome installation by Buckminster Fuller.

Behind the Frame: Picasso, Barack, and Me

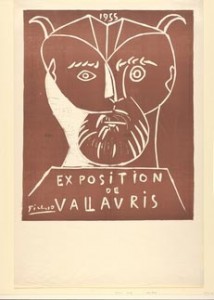

Pablo Picasso. Vallauris Exposition 1955 (1955 Exposition de Vallauris). 1955. Linoleum cut, 26 x 21 1/8" (66 x 53.7 cm), sheet: 35 1/4 x 23 3/8" (89.5 x 59.4 cm). Printer: Arnéra. Publisher: Arnéra. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Mr. and Mrs. Charles Kramer Collection, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Kramer. © 2010 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A few months back I was perusing The New York Times when I was stopped in my tracks by a picture of Barack Obama in his office at the University of Chicago. Being a former Second City citizen, I immediately felt a sense of kinship of place, but I was even more astonished to see hanging in his office the exact same Picasso print—a black and white devil-like image, a poster for 1955 Exposition de Vallauris—that hangs on the wall of my living room. I always look around people’s homes and offices for signs of who they are and what choices they make, but when I saw that Picasso work, I knew that Barack and I clearly had affinities! Not everyone makes the same choices or likes the same things—but we chose the same image to look at day in and day out. What did that say about us?

I had bought that print, probably not a “real” print, when I was seventeen years old. Pablo Picasso was perhaps my first real love. Growing up in Niagara Falls, Canada, where there is a wax museum literally on every corner (no wonder I ended up in this line of work!), I first met Picasso at the public library. The art section of the Dewey Decimal system was like my private zip code. I remember finding book about Picasso and Gertrude Stein and falling into a deep, deep swoon. I imagined myself living the salon life, with every conversation, morsel of food, or flirtation the catalyst for a painting or poem. My paintings, made late in the night, the only time an artist can work (teen or not), were inflected with Picasso’s lines, colors, and passions. Picasso sustained me through my teenage years. However, as I was indoctrinated into the art world of the mid-1970s during art school, I quickly came to realize that not only was my Picasso-influenced work not cool, but that he didn’t wear very well. I secretly pined in front of Guernica for my lost love during the obligatory visit to MoMA with my fellow students and professors.

Museum Kids: Keeping It Real

Ethan is delighted by the Formula 1 Racing Car hanging in the Education and Research building lobby.

Just after I’d accepted my job at MoMA, I brought my six-year-old son along with me to visit. He entered the Marron Atrium and, with a sweeping, 360-degree review and an air of finality, announced, “I like your new museum, mom.” Good thing it passed muster.

I often wonder what it is to grow up in a museum. From the time he was two, Ethan had a steady diet of contemporary art. Bridges made of Meccano sets; entire cities built of pots and pans; rooms glowing with neon tubes; walls covered with “parades” of people made from ripped black construction paper; cars and trailers jack-knifed, emerging out of a museum plaza; metal squares on the floor, perfect for playing hopscotch—to Ethan, art always seems full of possibilities.

His own “work” attests to that, as we find colored-tape installations proliferating throughout our apartment—often accompanied by an objet trouvé repurposed in interesting ways, or a small love note to mom and dad.

Ethan, now nine, accompanied me to the office last week.

If you are interested in reproducing images from The Museum of Modern Art web site, please visit the Image Permissions page (www.moma.org/permissions). For additional information about using content from MoMA.org, please visit About this Site (www.moma.org/site).

© Copyright 2016 The Museum of Modern Art