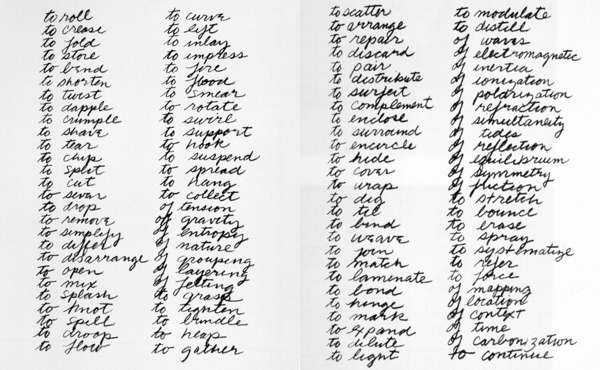

Richard Serra. Verb List. 1967–68. Graphite on paper, 2 sheets, each 10 x 8" (25.4 x 20.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist in honor of Wynn Kramarsky. © 2011 Richard Serra/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Serra has talked at length, for example, about the central place this language-based drawing occupied in the development of his early sculpture. “When I first started, what was very, very important to me was dealing with the nature of process,” he said. “So what I had done is I’d written a verb list: to roll, to fold, to cut, to dangle, to twist…and I really just worked out pieces in relation to the verb list physically in a space.” A sort of linguistic laying out of possible artistic options, this work on paper functioned for the artist “as a way of applying various activities to unspecified materials.”

One of these materials was rubber. In the 1967 sculpture To Lift</a>, Serra performed that titular action on a piece of vulcanized rubber recovered from a downtown warehouse. While some combinations of verb and material yielded uninteresting results, this particular outcome fascinated the artist, since the action of its making remained clearly visible in the product. The subsequent Castings and Splashings of the late 1960s—in which Serra flung molten lead into the intersection between wall and floor—were similarly sprung from verbs.</p>

But while Serra is primarily known as a sculptor—and certainly his more recent monumental steel ellipses not only twist, curve, and swirl, but also enclose, surround, and encircle—the verbs in this list have been influential across his body of work. Films like Hand Catching Lead and Hand Scraping (both 1968) show a single repeated action. And the thick texture of his paintstick drawings evidence the vigorousness of the artist’s application. As important as the Verb List has been for Serra specifically, it’s also a more largely emblematic work for MoMA to acquire at this moment; I can’t help but think about it in relation to recent exhibitions and trends on 53rd Street. In light of the Museum’s recent Abstract Expressionist New York exhibition, it’s worthwhile considering Serra’s debt to action painting, underscored here by the inclusion of verbs like to dapple, to spill, and to spray. In the context of a recent commitment to performance, Serra’s shared concerns with dancer contemporaries like Yvonne Rainer and Simone Forti come to the fore. And a renewed interest at MoMA in Conceptual art, highlighted by the recent acquisition of the Seth Siegelaub and Herman and Nicole Daled archives, reminds us to consider the significance of the site of Verb List’s original 1971 publication: the Conceptual art journal Avalanche.