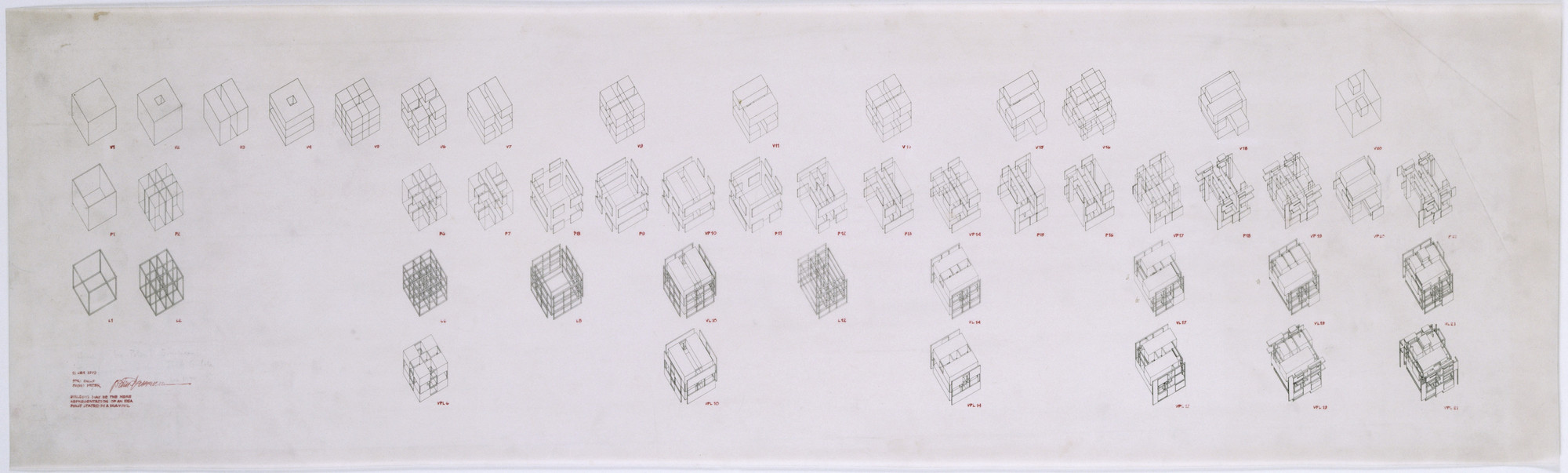

In numerous texts and a series of eleven houses, Eisenman expounded his theory of an autonomous architecture in which form need not respond to specific requirements. Here, architecture takes on an intellectual role that is distanced from the constraints of reality—a seemingly apolitical attitude that is itself an entrenched statement on the cultural power of design. Thus, elements such as columns and walls are separated from an aesthetic and functional context and used as part of a notational system. The inscription at the lower left of this work —“Building may be the mere representation of an idea first stated in drawing”—indicates the primacy of drawing in Eisenman’s thought process. The sequence of axonometric drawings acts as a diagram for the transformation of a basic cube into a highly developed spatial configuration; shelter is the result of cerebral processes that speak of architecture’s ability to generate its own logic and authority.

Gallery label from 9 + 1 Ways of Being Political: 50 Years of Political Stances in Architecture and Urban Design, September 12, 2012–March 25, 2013.

Through a series of eleven houses designed in the late 1960s and 1970s and as the author of numerous texts, Peter Eisenman expounded his theory of an autonomous architecture in which it was no longer necessary for architectural form to result from specific programmatic requirements. Eisenman called these works "cardboard architecture" to describe the way elements such as columns and walls were separated from an "aesthetic and functional context," being used instead as part of a "marking or notational system." To explain the underlying structure of "finite elements" on which his forms were based, Eisenman used the term "deep structure," borrowed from linguistic theory.

The inscription at the lower left of this drawing, "Building may be the mere representation of an idea first stated in a drawing," intimates the importance of drawing in Eisenman's design process. This sequence of axonometrics acts as a diagram, illustrating the transformation of a basic cube into a highly developed spatial configuration. Eisenman has explained, "The diagrams began from a series of rule systems that once set in motion would begin to change the very nature of the rule system itself. The generative rule system would bring about a series of moves, like in a game of chess, in which each move is a response to the last." The original cube was cut, extended, and rotated until the final form of House IV was achieved.

Eisenman first used the concept of the diagram in his Ph.D. thesis in 1963, and it continues to play an important role in his work. Recent projects drawing upon the ideas of philosophers Jacques Derrida and Gilles Deleuze explore the potential of the diagram as an image that is used to create form yet is not in itself a representation of that form.

Publication excerpt from an essay by Melanie Domino, in Matilda McQuaid, ed., Envisioning Architecture: Drawings from The Museum of Modern Art, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2002, p. 180.