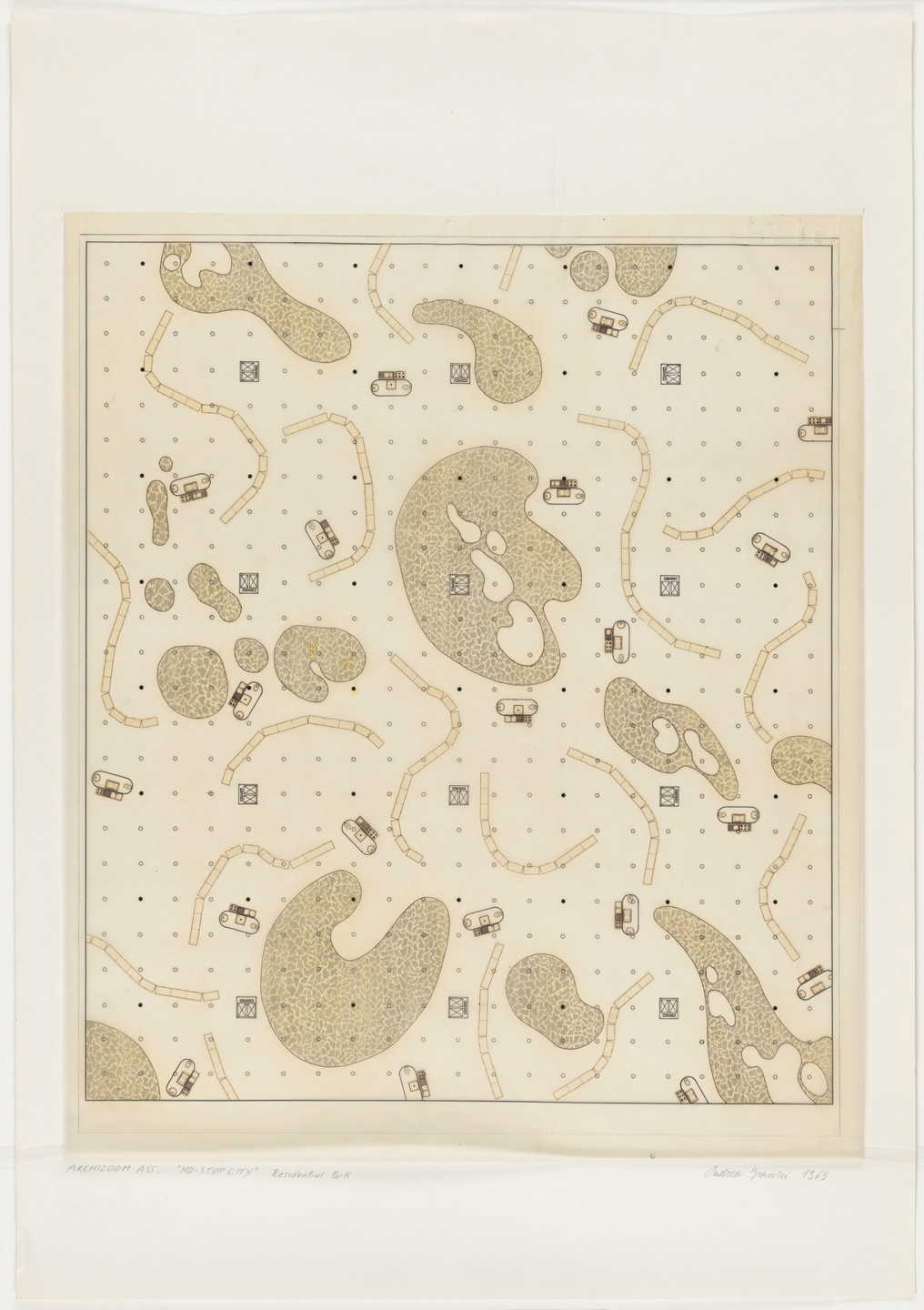

Branzi founded the Italian avant-garde group Archizoom in 1966 with Gilberto Corretti, Paolo Deganello, and Massimo Morozzi. Like other radical architecture groups of the 1960s, it reacted against modernist architecture and downplayed practical concerns in favor of an imaginative, science-fiction-like approach. No-Stop City is based on the idea that advanced technology could eliminate the need for a centralized modern city. This plan illustrates a fragment of a metropolis that can be extended infinitely through the addition of homogenous elements adapted to a variety of uses. Residential units and free-form organic shapes representing parks are placed haphazardly over a grid structure, allowing for a large degree of freedom within a regulated system. Strongly ironic but designed with committed political ingenuity, the proposal questions the normative character of the existing city and defends new conceptions of life as expressed in revolutionary urban form.

Gallery label from 9 + 1 Ways of Being Political: 50 Years of Political Stances in Architecture and Urban Design, September 12, 2012–March 25, 2013.

Andrea Branzi, Gilberto Corretti, Paolo Deganello, and Massimo Morozzi founded the Italian avant-garde group Archizoom in 1966. They were inspired by the architectural group Archigram, and by its technological projects for urban utopias; in fact they took their name in part from the name of the British group and in part from the title—_Zoom—_of an issue of the publication Archigram. Archizoom was a key participant in the "radical architecture" movement of the 1960s, which reacted against modernist architecture and downplayed practical concerns in favor of a more imaginative, science-fiction-like approach.

The principle behind the No-Stop City was the idea that advanced technology could eliminate the need for a centralized modern city. The group members wrote, "The factory and the supermarket become the specimen models of the future city: optimal urban structures, potentially limitless, where human functions are arranged spontaneously in a free field, made uniform by a system of micro-acclimatization and optimal circulation of information." The drawings and photomontages that constitute the project were intended to demonstrate these ideas rather than to serve as the plan for an actual city. This plan, drawn by Branzi, illustrates a fragment of a metropolis that can extend infinitely through the addition of homogenous elements adapted to a variety of uses. Free-form organic shapes—representing park areas—and residential units are placed haphazardly over a grid structure, allowing for a large degree of freedom within a regulated system. Like a replicating microorganism, the city seems to subdivide and spread, lacking center or periphery.

Publication excerpt from an essay by Melanie Domino, in Matilda McQuaid, ed., Envisioning Architecture: Drawings from The Museum of Modern Art, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2002, p. 158.

Andrea Branzi, a founding member of Archizoom, the Italian avant-garde architectural group begun in 1966, was inspired by the urban utopias of the British group Archigram. His Residential Park, No-Stop City, like other works of Archizoom, is a reaction against modernist architecture that explores the imaginative at the expense of the practical. In this drawing, which presents an idea rather than an actual plan, technology eliminates the need for a centralized city. Biomorphic forms, placed haphazardly over an infinitely extendable grid represent acclimatized microenvironments, for example, green amoeba-like forms are parks, and the serpentine strings are housing units.

Publication excerpt from an essay by Bevin Cline and Tina di Carlo, in Terence Riley, ed., The Changing of the Avant-Garde: Visionary Architectural Drawings from the Howard Gilman Collection, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2002.