“To put it another way, my work is an attempt...to give meaning to the ephemeral. To do this, obviously, I have to freeze the instant itself.”

Mira Schendel

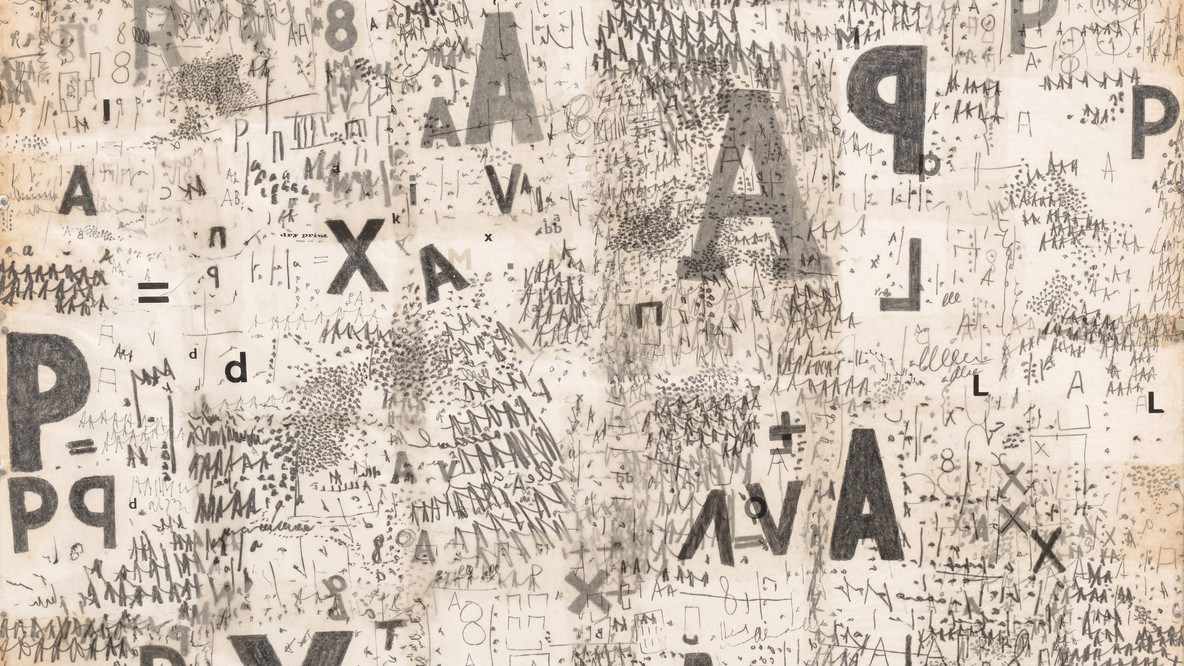

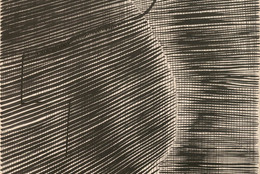

In the early 1960s, the artist Mira Schendel received a large gift of thin Japanese paper. It transformed her practice, giving rise to thousands of Monotipias and culminating in her Objetos gráficos of the 1970s, made while she dedicated a decade to the investigation of the medium of drawing and its potential. The obsessive yet delicate qualities of these works ranged from a single thin line pressed into a page to dense, teeming layers of marks and symbols trapped between acrylic sheets.

Schendel was keenly aware of the barriers that language and culture could create between people. Because of her Jewish heritage, in 1939 the Italian government revoked her student visa and forced her to find another country. By the time she immigrated to Brazil in 1949, she had lived in three countries and spoke six languages. As a European immigrant to Brazil, a student of philosophy, and a bibliophile, Schendel found her affinities to be more often in line with poets, theologians, and scientists than with the artists in the Concrete-art movements that dominated the art world in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in the 1950s. In the early 1960s, she continued to delve into the larger philosophical questions of life in her work, while simultaneously pushing at the edges of drawing, printing, and sculpture.

Objetos gráficos powerfully demonstrate her singular approach. The works comprise sheets of Japanese rice paper that were marked with printed, typewritten, and/or dry-transferred letters and numbers, symbols, and signs. The sheets were then arranged in overlapping grids pressed between two pieces of clear acrylic and hung from the ceiling, transforming the artist’s marking and ordering gestures into free-floating objects.

The artist remarked that the acrylic enabled her to “concretize an idea, the idea of doing away with back and front, before and after.” The fusion of drawing and sculpture changes the relationship between the viewer and the work: “It allows for a circular reading with the texts as the unmovable center and the reader in motion,” Schendel explained.

For those who encounter these works, language is neither readable nor completely unreadable, but presented as an intuitive, poetic, and physical experience. Schendel said the works were “an attempt to bring about drawing through transparency.” Her experiments give density and form to both the metaphysical questions of life and the difficult search for answers.

Note: The opening quote is from Mira Schendel's typed manuscript, unsigned and undated from the Arquivo Mira Schendel, reprinted in Luis Pérez-Oramas, ed., Tangled Alphabets: León Ferrari and Mira Schendel exh.cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 60.

Beverly Adams, The Estrellita Brodsky Curator of Latin American Art, Department of Painting and Sculpture, 2022

“Dicho de otro modo, mi obra es un intento...de dar sentido a lo efímero. Para eso, obviamente tengo que congelar el propio instante.”

Mira Schendel

A principios de los años sesenta, la artista Mira Schendel recibió una gran cantidad de papel japonés de regalo. Esto transformó su obra, dando lugar a miles de Monotipias y culminando en sus Objetos gráficos, realizados a lo largo de la década del setenta, dedicada a investigar el medio del dibujo y su potencial. Los atributos obsesivos pero delicados de estas obras abarcaban desde una única línea delgada y comprimida en una página, hasta capas densas, repletas de marcas y símbolos atrapadas entre dos láminas de acrílico.

Schendel era sumamente consciente de las barreras que el idioma y la cultura pueden manifestar entre las personas. En 1939, debido a su origen judío, el gobierno italiano le retiró el visado de estudiante y la obligó a buscar otro país. En 1949, cuando finalmente emigró a Brasil, había vivido en tres países y hablaba seis idiomas. Como inmigrante europea en Brasil, estudiante de filosofía y bibliófila, Schendel se sentía más afín a los poetas, teólogos y científicos que a los artistas de los movimientos de arte concreto que dominaban la escena del arte en São Paulo y Río de Janeiro en la década de 1950. A principios de la década de 1960, siguió profundizando sobre los grandes interrogantes filosóficos de la vida en su obra, experimentando simultáneamente con los límites del dibujo, la estampa y la escultura.

Los Objetos gráficos son una contundente demostración de su singular enfoque. Las piezas están compuestas por láminas de papel de arroz japonés marcadas con letras, números, símbolos y signos impresos, mecanografiados o transferidos en seco. Luego, las láminas fueron colocadas en cuadrículas superpuestas y prensadas entre dos piezas de acrílico transparente, y colgadas del techo, lo que transformó los gestos de marcaje y ordenamiento de la artista en objetos que flotan libremente.

La artista declaró que el acrílico le permitió “concretar una idea, la idea de acabar con el reverso y el anverso, el antes y el después”. La fusión del dibujo y la escultura modifica la relación entre el espectador y la obra: “Permite una lectura circular, con los textos como centro inamovible y el lector en movimiento", explicó Schendel.

Quien se encuentra frente a estas obras, descubre que el lenguaje no es ni legible ni completamente ilegible, sino que se presenta como una experiencia intuitiva, física y poética. Según Schendel, las piezas son “un intento por conseguir el dibujo a través de la transparencia”. Sus experimentos confieren densidad y forma a las preguntas metafísicas de la vida y a la ardua búsqueda de sus respuestas.

Nota: La cita inicial procede del manuscrito mecanografiado de Mira Schendel, sin firma ni fecha, en el Arquivo Mira Schendel, reimpreso en Luis Pérez-Oramas ed., Tangled Alphabets: León Ferrari and Mira Schendel, catálogo de la exposición (Museo de Arte Moderno, Nueva York, 2009), p. 60.

Beverly Adams, Curadora Estrellita Brodsky de Arte Latinoamericano, Departamento de Pintura y Escultura, 2022.

Traducido por Carmen M. Cáceres

![Simon Hantaï. Untitled [Suite "Blancs"]. 1973. Acrylic on canvas, 10' 1/4" x 15' 3 1/4" (305.3 x 466.5 cm). Acquired through the Carol Buttenwieser Loeb and Arnold A. Saltzman Funds](/d/assets/W1siZiIsIjIwMjMvMDMvMDYvNHRrc254ZHRyY18xMDNfMTk4Ml9hX2JfQ0NDUl9QcmVzc19TaXRlLmpwZyJdLFsicCIsImNvbnZlcnQiLCItcXVhbGl0eSA5MCAtcmVzaXplIDI2MHgxNzReIC1ncmF2aXR5IENlbnRlciAtY3JvcCAyNjB4MTc0KzArMCJdXQ/103_1982_a-b_CCCR-Press%20Site.jpg?sha=6223176e15e309da)