“The camera is not the obstacle, it is one’s self!”

Kati Horna

“I fled Hungary, I fled Berlin, I fled Paris, and I left everything behind in Barcelona,” the photographer Kati Horna remarked near the end of her life. Associating a sense of itinerancy and exile with her chosen medium, she added, “It’s for vagabonds like me. Because my clothes got torn on the route, I selected photography.” For Horna, photography represented not only a career that could translate across borders, but a form of political and artistic expression. She used the medium to render visible social relations and reflect on her own trajectory from Budapest to Mexico City, where she lived among a community of European artists after 1939.

Horna (née Katalin Deutsch) was born to an affluent Jewish family in Budapest in 1912, and as a teenager became involved in the left-wing political circle around the Hungarian artist Lajos Kassák. She went to Berlin to pursue a degree in politics, but the rise of Adolf Hitler forced her to return to Budapest, where she enrolled in a course with the well-known modernist photographer Józef Pésci. In September 1933, she moved to Paris (with her first husband, a Hungarian antifascist activist named Paul Partos), finding work as a freelance photographer for a press picture agency, Agence Photo.

One of her earliest series centered on Parisian flea markets, a subject widely surveyed by other foreign-born photographers like André Kertész, Brassaï, and Germaine Krull. At first glance, Man and Candlesticks (c. 1933), a photograph from the series, seems to be a straightforward depiction of a salesman trafficking in brass goods. In the top left corner, an out-of-focus hand holds up something before the man, who peers back at it intently. Including the hand in the frame, Horna uses the camera to involve the viewer in the exchange and conjure the embodied experience of the flea market. Horna’s political upbringing in Budapest and Berlin, as well as her artistic tutelage under Pésci, had given her the tools to capture the subtle, ironic, and often strange complexities of urban life and modern relationships structured around exchange.

Spurred by a leftist social consciousness, Horna left Paris in 1937 to cover the events of the Spanish Civil War. Her childhood friend, the Hungarian photojournalist Robert Capa, was also drawn to the conflict, documenting the struggle between Franco’s right-wing military forces and the Spanish Republicans in iconic images like Death of a Loyalist Militiaman, Córdoba front, Spain. Instead of the battlefront, Horna focused on the material conditions of women and children in war-torn Spain, and became involved with anarchist movements in the Catalan and Aragon regions. Horna’s Los Paraguas, mitin de la CNT (Umbrellas, Meeting of the CNT), Spanish Civil War, Barcelona shows a crowd from above. Sporting umbrellas, they gather in the street for a rally organized by the anarchist trade union, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (National Confederation of Labor), or CNT. Calling for a true worker’s revolution, the CNT opposed Franco’s dictatorship, while remaining skeptical of both its allies in the Republican government and the Stalin-backed Communist leaders in Catalan. Horna supported their efforts, designing a dynamic brochure commissioned by the Foreign Propaganda Office of the CNT and working as a photojournalist for a series of anarcho-syndicalist publications, including the feminist journal Mujeres Libres, the CNT’s cultural magazine Libre Studio, and the Valencia-based anarchist newspaper Umbral. In the offices of Umbral, she met her second husband, the sculptor José Horna.

Following a brief return to Paris, Horna was once again forced to flee. She and José left Europe at the outbreak of World War II, settling in Mexico City, where the couple became part of a community of exiled European artists, including French Surrealist poet Benjamin Péret, English painter Leonora Carrington, and Spanish painter Remedios Varo. The closeness of this circle is evident in Horna’s 1962 portrait of Varo wearing a mask made by Carrington.

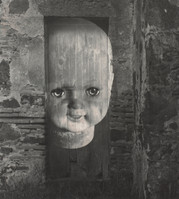

Horna’s Paris work had betrayed a surrealist sensibility, not only through the sense of estrangement in her pictures of flea markets and popular cafés, but in works such as Doll Parts (c. 1938). Deploying the technique of superimposition, she created uncanny studies of dismembered doll bodies, linking her to Surrealist artists like Hans Bellmer. While Horna claimed to have read the work of the movement’s leader, André Breton, she asserted that she “never went to the Café de Flore or Montmartre” where the group often gathered. Yet Horna participated fully in the version of Surrealism that flourished in Mexico, creating works such as Bottle (1962). A photograph of a woman’s upper torso distorted through a glass jug, it was part of a series for the short-lived avant-garde magazine, S.nob.

Surrealism, politics, and sense of place inflected Horna’s career as a teacher in Mexico, influencing the work of students such as Flor Garduño. And, as Horna’s daughter observed, she presented photography to her students “as a tool for the recovery of memory—indeed, for her, photography made it possible to rescue from oblivion the losses that marked her life.”

Caitlin Ryan, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography, 2021

Note: the opening quote is translated from Spanish, as quoted in Tranche, Rafael R; Sánchez-Biosca, Vicente; and Nancy, Berthier, “Kati Horna. El compromiso de la mirada. Fotografías de la guerra civil española (1937–1938).” In Iberic@l: revue d’études ibériques et ibéro-américaines no. 1 (January 2012), 138.