“My work is really about generating reflection. I want to understand the context of the period, the social conditions of the period.”

Leandro Katz

“All my reservations about being in the United States dissolved when I got to New York, when I saw that ebullience and started meeting people,” said the artist Leandro Katz. “I started to realize that we were living in a moment of absolute effervescence.”

Born in Argentina, Katz arrived in New York in 1965. As a poet, translator, Conceptual artist, and professor, Katz participated in experimental literary movements in Buenos Aires, Quito, Lima, and New York. Coming to the end of a winding path through South and Central America, in New York he found a thriving community of avant-garde artists and activists. He made the city his home for over 40 years.

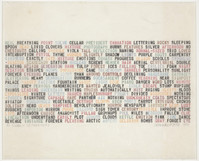

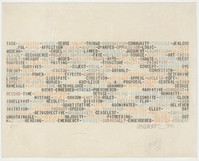

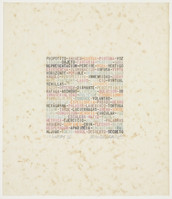

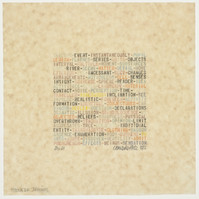

During his travels in the summer of 1963, Katz had encountered the monumental ruins of the ancient Maya in southern Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras. The experience shaped his relationship to language, especially as he adapted to living in the United States. Like many Conceptual artists, he developed an interest in symbolic systems of representation. His text-based works from the early 1970s share the analytical approach of friends and collaborators Mel Bochner and Lawrence Weiner. In his drawings 21 and 21 × 78 Characters, Katz arranges English texts by inventing a geometric, rather than grammatical, structure: 21 lines of 78 characters each. Similarly, in 21 Lineas I, 21 Lineas II, 21 Lineas III, and 21 Lineas IV, each drawing contains a square of typewritten Spanish words in 21 lines, where each line measures 21 centimeters. The meanings that might emerge from the words, sounds, and colors juxtaposed to fit these criteria, rather than syntactic rules, are accidental.

“I became very absorbed with the Maya because of my interest in image and text,” Katz has said. The meanings embedded in the Mayan alphabet, which was largely destroyed during the Spanish conquest, had at the time been only partially decoded. “The mystery of the Maya hieroglyphs is the question: is it a phonetic, ideographic, or pictographic system; are they things that represent things or things that represent ideas or phonetic expressions representing sounds and eventually words. I realized that I, as a poet-artist, was trying to do something similar to what they were doing: to express ideas with gestures that varied between the rational and the divinatory, between the phonetic and the sensorial.”

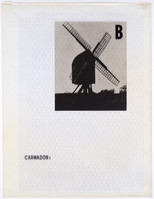

These questions converge in his invented alphabets: 27 Molinos (27 Windmills), in which images of windmills that he photographed in Spain and Portugal stand in for the letters of the Latin alphabet, and his Lunar Alphabets, in which letters are replaced by the phases of the moon. With allusions to Maya astronomy and the Spanish novel Don Quixote, respectively, Katz proposes a poetic register of meanings lurking just below the level of words. His Lunar Sentence II, from 1978, reads, “When we pulverize words, what is left is neither mere noise nor arbitrary pure elements, but still other words, reflection of an invisible and yet indelible representation: this is the myth in which we now transcribe the most obscure and real powers of language.”

In 1984, Katz returned to the Yucatán region to photograph the Maya monuments. This time, his expedition retraced the journey of 19th-century explorers John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood, the first English-speaking travelers in the region originally inhabited by the Maya. Their bestselling travelogues—including Catherwood’s painstakingly accurate drawings, made with the help of a camera lucida—popularized and romanticized the Maya in the US and Europe. But, Katz has said, “the European eye coins the culture in its own terms,” and in The Catherwood Project he set out to investigate their representations of the ancient sites by reconstructing Catherwood’s precise point of view.

Some photographs, such as Uxmal, after Catherwood [House of the Nuns, Southeast Corner] and Labná Arch, after Catherwood [East Façade], pair Catherwood’s and Katz’s images to reveal the passage of centuries and the artist’s manipulation of the image. In others, such as The Castle [Chichén Itzá] and Tulúm, a la manera de Catherwood (El Castillo) (Tulúm, after Catherwood [The Castle]), Katz acknowledges his own role in constructing these views, including his own hand holding Catherwood’s lithograph in the image. “I cannot deny my own manipulation of reality. I, too, am representing,” he said. Finally, photographs such as Templo de la Frondosa Cruz, Palenque (Temple of the Foliated Cross, Palenque) do not directly quote Catherwood’s representation, but replicate the dark palette and atmospheric skies of his expeditionary gaze. Now crowded with tourists rather than overgrown vegetation, the monuments, like words, refer to something shifting and elusive. Throughout his career, across many mediums, Katz has sought to uncover the many layers of meaning existing within image and text. Tilting at windmills, divining the moon, or encountering ancient ruins, we see what we want to see.

Note: Opening quote is from the MoMA Audio stop for Leandro Katz. The Castle [Chichén Itzá]. 1985, https://www.moma.org/audio/4361.

Julia Detchon, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Drawings and Prints, 2024

“Todas mis reservas sobre estar en Estados Unidos se disuelven cuando llego a Nueva York, veo esa ebullición y comienzo a conocer gente”, dijo el artista Leandro Katz. “Empecé́ a darme cuenta de que estábamos viviendo un momento de efervescencia absoluta”.

Katz nació en Argentina y llegó a Nueva York en 1965. Como poeta, traductor, artista conceptual y profesor, participó en movimientos de experimentación literaria en Buenos Aires, Quito, Lima y Nueva York. Tras un sinuoso periplo por Sur y Centroamérica, en Nueva York encontró una próspera comunidad de artistas y activistas de vanguardia. La ciudad se convirtió en su hogar por más de cuarenta años.

Durante viajes realizados en el verano de 1963, Katz visitó las monumentales ruinas de los antiguos mayas al sur de México, Guatemala y Honduras. La experiencia marcó su relación con el idioma, sobre todo cuando tuvo que adaptarse a la vida en los Estados Unidos. Como muchos otros artistas conceptuales, sentía un gran interés por los sistemas de representación simbólica. Sus obras de principios de la década de 1970, basadas en textos, comparten el enfoque analítico de sus amigos y colaboradores Mel Bochner y Lawrence Weiner. En sus dibujos 21 y 21 x 78 Caracteres, Katz ordena los textos en inglés asignándoles una estructura geométrica, en lugar de una gramatical: 21 líneas de 78 caracteres para cada una. Algo parecido hace en 21 Lineas I, 21 Lineas II, 21 Lineas III y 21 Lineas IV, donde cada dibujo consiste en un cuadrado de palabras mecanografiadas en español y dispuestas en 21 líneas, de 21 centímetros cada una. Cualquier sentido que pudiese surgir de las palabras, sonidos y colores yuxtapuestos para cumplir con esos criterios (más que con las reglas sintácticas) es fortuito.

“Me interesé mucho por los mayas debido a que estaba interesado en la combinación texto-imagen”, ha dicho Katz. Por entonces, los significados inscritos en el alfabeto maya —en gran parte destruido durante la conquista española— sólo se habían descifrado parcialmente. “El misterio de los jeroglíficos mayas era la pregunta: si era un sistema fonético, ideográfico o pictográfico; si eran cosas que representaban cosas o si eran cosas que representaban ideas o si eran expresiones fonéticas que representaban sonidos y eventualmente palabras…dándome cuenta que yo, como poeta-artista, estaba tratando de hacer algo similar a lo que ellos hacían: expresar ideas desde gestos que variaban entre gestos racionales y gestos adivinatorios, gestos fonéticos y gestos sensoriales”.

Estas inquietudes confluyen en sus alfabetos inventados: 27 Molinos (27 Windmills), en el que distintas imágenes de molinos de viento fotografiados en España y Portugal sustituyen a las letras del alfabeto latino, y en sus Alfabetos Lunares, en los que las fases de la luna reemplazan a las letras. Aludiendo a la astronomía maya y a la novela española El Quijote, respectivamente, Katz propone un registro poético de significados que acechan justo debajo del plano de las palabras. En su obra Lunar Sentence II (1978) se puede leer: “Cuando pulverizamos las palabras, lo que queda no es mero ruido ni arbitrariedad, que son puro elemento, sino otras, nuevas palabras, reflejo de una representación invisible a la vez que indeleble: éste es el mito sobre el cual ahora transcribimos los poderes más oscuros y reales del lenguaje”.

En 1984, Katz regresó a la península de Yucatán para fotografiar los monumentos mayas. En esa ocasión, la expedición siguió los pasos de los exploradores John Lloyd Stephens y Frederick Catherwood en el siglo XIX, los primeros viajeros angloparlantes en aquella región originalmente habitada por los mayas. Sus exitosos diarios de viaje –que incluían los dibujos rigurosos y precisos de Catherwood, realizados con la ayuda de una cámara lúcida– habían popularizado y romantizado la civilización Maya en Estados Unidos y Europa. Pero, según Katz: “el ojo europeo acuña la cultura en sus propios términos”, y en The Catherwood Project se propuso indagar en esas representaciones de los antiguos yacimientos reconstruyendo con precisión el punto de vista de Catherwood.

Algunas fotografías, como Uxmal, after Catherwood [House of the Nuns, Southeast Corner] y Labná Arch, after Catherwood [East Façade], combinan imágenes de Catherwood y de Katz para evidenciar el paso de los siglos y la manipulación que hacen los artistas de las imágenes. En otras, como The Castle [Chichén Itzá] y Tulúm, a la manera de Catherwood (El Castillo) (Tulúm, after Catherwood [The Castle]), Katz admite su propio papel en la construcción de estas impresiones, incluyendo en la imagen su mano, mientras sostiene una litografía de Catherwood. “No puedo negar mi propia manipulación de la realidad. Yo también estoy representando”, dijo. Por último, fotografías como Templo de la Frondosa Cruz, Palenque no citan directamente la representación de Catherwood, pero reproducen la paleta oscura y los cielos atmosféricos de su mirada de explorador. En la actualidad, más llenos de turistas que de vegetación crecida, los monumentos —al igual que las palabras— remiten a algo cambiante y evasivo. A lo largo de su carrera, y a través de distintos medios, Katz ha intentado desvelar las múltiples capas de significados escondidos en el interior de la imagen y del texto. Cuando luchamos contra molinos de viento, adivinamos los ciclos de la luna o encontramos ruinas antiguas, sólo vemos lo que queremos ver.

Julia Detchon, Asistente Curatorial, Departamento de Dibujos y Grabados, 2024

![Leandro Katz. Tulúm, after Catherwood [The Castle]. 1985. Gelatin silver print, 16 × 20" (40.6 × 50.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Promised gift of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros through the Latin American and Caribbean Fund in honor of May Castleberry. © 2024 Leandro Katz](/d/assets/W1siZiIsIjIwMjQvMDMvMjgvODBqNnd6MHluOV8wM18yNl8yNF9MZWFuZHJvX0thdHpfUEc3MjEuMjAxN19BcnRpc3RfQmlvc19LZXlfUmVwcmVzZW50YXRpdmVfSW1hZ2UuanBnIl0sWyJwIiwiY29udmVydCIsIi1xdWFsaXR5IDkwIC1yZXNpemUgMTE4NHg2NjZeIC1ncmF2aXR5IENlbnRlciAtY3JvcCAxMTg0eDY2NiswKzAiXV0/03-26-24_Leandro-Katz_PG721.2017_Artist-Bios_Key-Representative-Image.jpg?sha=00fd8b3cc90eb1e0)

![The Castle [Chichén Itzá]](/d/assets/W1siZiIsIjIwMjMvMDMvMjMvOG5idG42MGJucF9QRzcyMC4yMDE3X2thdHouanBnIl0sWyJwIiwiY29udmVydCIsIi1xdWFsaXR5IDkwIC1yZXNpemUgMTU4eDEwNV4gLWdyYXZpdHkgQ2VudGVyIC1jcm9wIDE1OHgxMDUrMCswIl1d/PG720.2017_katz.jpg?sha=12a83af791729e9b)