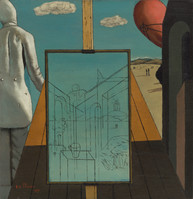

“What is especially needed is great sensitivity: to look upon everything in the world as enigma…”

Giorgio de Chirico

“What is especially needed is great sensitivity: to look upon everything in the world as enigma….To live in the world as in an immense museum of strange things.” So wrote the Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico, who made paintings of classical piazzas populated with spectral figures and shadows, knitting together purposefully distorted perspectives and tilted grounds. These claustrophobic dreamscapes, with their atmosphere of melancholy and uneasy menace, captivated the French avant-garde of the 1910s and later inspired the Surrealists.

Arriving in Paris in 1911, de Chirico immersed himself in the city’s avant-garde circles. Guillaume Apollinaire, the experimental poet and defender of Cubism, soon became the artist’s champion, writing in an early review of a small exhibition de Chirico staged in his studio, “The art of this young painter is an interior and cerebral art which bears no relation to that of the painters of recent years.” (De Chirico would later encourage this perception of himself as an outsider.) Apollinaire also noted that de Chirico’s “very sharp and very modern sensations” often assumed an “architectural form,” perhaps in reference to The Anxious Journey, with its overlapping colonnades, which was included in that exhibition.

In The Enigma of a Day, painted a year after The Anxious Journey, in 1914, de Chirico took up the motifs of his previous composition and expanded them. The sharply delineated shadows and sun-bleached arcades now framed a piazza, deserted but for a towering marble statue, a partially obscured moving carriage, and two human figures casting exaggerated shadows in the distance. One of de Chirico’s great innovations was to marry these vaguely classical, if highly simplified, architectural elements with the recently developed pictorial language of Cubism, typified by flattened spatial structures, shapes reduced to bold and simple planes, muted tones with little modeling, and compressed space. Another hallmark of his style was a seemingly effortless conjunction of incompatible spatial systems into a single, coherent scene. In The Enigma of a Day, he plays with both shallow and steep spaces and employs numerous vanishing points. These spatial inconsistencies only reveal themselves on close examination, undermining any initial impression of stability.

In 1917, recently returned to Italy, de Chirico founded the Scuola Metafisica (or Metaphysical School), formulating its principles with his brother Alberto Savinio and the Futurist artist Carlo Carrà. De Chirico compared the metaphysical work of art to “the flat surface of a perfectly calm ocean,” which “disturbs us…by all the unknown that is hidden in the depth.” The term would come to encompass all his work produced between roughly 1911 and 1917; it is this “metaphysical” period that would prove highly influential to the Surrealists in the following decade.

Led by André Breton, himself inspired by the writings of Sigmund Freud, Surrealism sought to give greater license to the irrational forces of the unconscious and to represent this artistically through what Breton described as the poetic “juxtaposition of two realities.” In paintings like The Song of Love, with its incongruous combination of familiar objects, the Surrealists saw an important precedent; indeed, Breton later called de Chirico a “sentry.” But even as the Surrealists collected and exhibited de Chirico’s paintings from the 1910s, the artist himself had left that work behind, calling for a return to skilled drawing in an apparent about-face that provoked their scorn.

Natalie Dupêcher, independent scholar, 2017

![Eliot Porter. Blue-throated Hummingbird, Chiricahua Mountains, Arizona, May 1959 [Lampornis clemenciae]. 1959. Dye transfer print, 9 5/16 × 7 3/4″ (23.7 × 19.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of David H. McAlpin. © 1990 Amon Carter Museum of American Art](/d/assets/W1siZiIsIjIwMTUvMTAvMjAvMmFrMGQ4MGJjN19BcnRpc3RzQ2hvaWNlVHJpc2hhLmpwZyJdLFsicCIsImNvbnZlcnQiLCItcXVhbGl0eSA5MCAtcmVzaXplIDI2MHgxNzReIC1ncmF2aXR5IENlbnRlciAtY3JvcCAyNjB4MTc0KzArMCJdXQ/ArtistsChoiceTrisha.jpg?sha=705aeaabfd354707)